Ireland, the Emerald Isle, beckons with its verdant landscapes and the haunting echoes of a past as rich as it is turbulent. More than just picturesque scenery, its history is a tapestry woven with threads of ancient myths, fierce struggles for self-determination, and profound cultural resilience. This comprehensive guide aims to unravel the intricate saga of Ireland’s journey, from its mysterious ancient origins to the fierce fight for its independence, and the enduring complexities of the Northern Ireland conflict. We’ll delve into the megalithic builders, the arrival of the Celts, the Golden Age of monasticism, Viking incursions, centuries of English rule, the devastating Famine, and the revolutionary movements that shaped a nation. Finally, we’ll examine the period known as the Troubles and the ongoing path to peace and reconciliation.

Echoes from the Mist: The Ancient History of Ireland

Pre-Celtic Ireland: Megalithic builders and early inhabitants

Long before the Celts, Ireland was home to sophisticated societies. The most remarkable evidence lies in the Boyne Valley, where monumental passage tombs like Newgrange stand as testaments to astronomical knowledge and engineering prowess dating back over 5,000 years, older than the pyramids of Egypt [1]. These early inhabitants lived in settled agricultural communities, their beliefs deeply intertwined with nature and the cosmos.

The Arrival of the Celts (c. 500 BCE)

The arrival of the Celts brought profound cultural shifts. Their distinct language, Gaelic, and rich mythology, populated by heroes like Cú Chulainn and mythical realms, became central to Irish identity. Society was structured around the ‘tuath’ (kingdom), governed by chieftains and guided by the intricate Brehon Laws, an ancient legal system. The Celts also introduced advanced ironworking techniques.

Early Christianity (c. 5th Century CE)

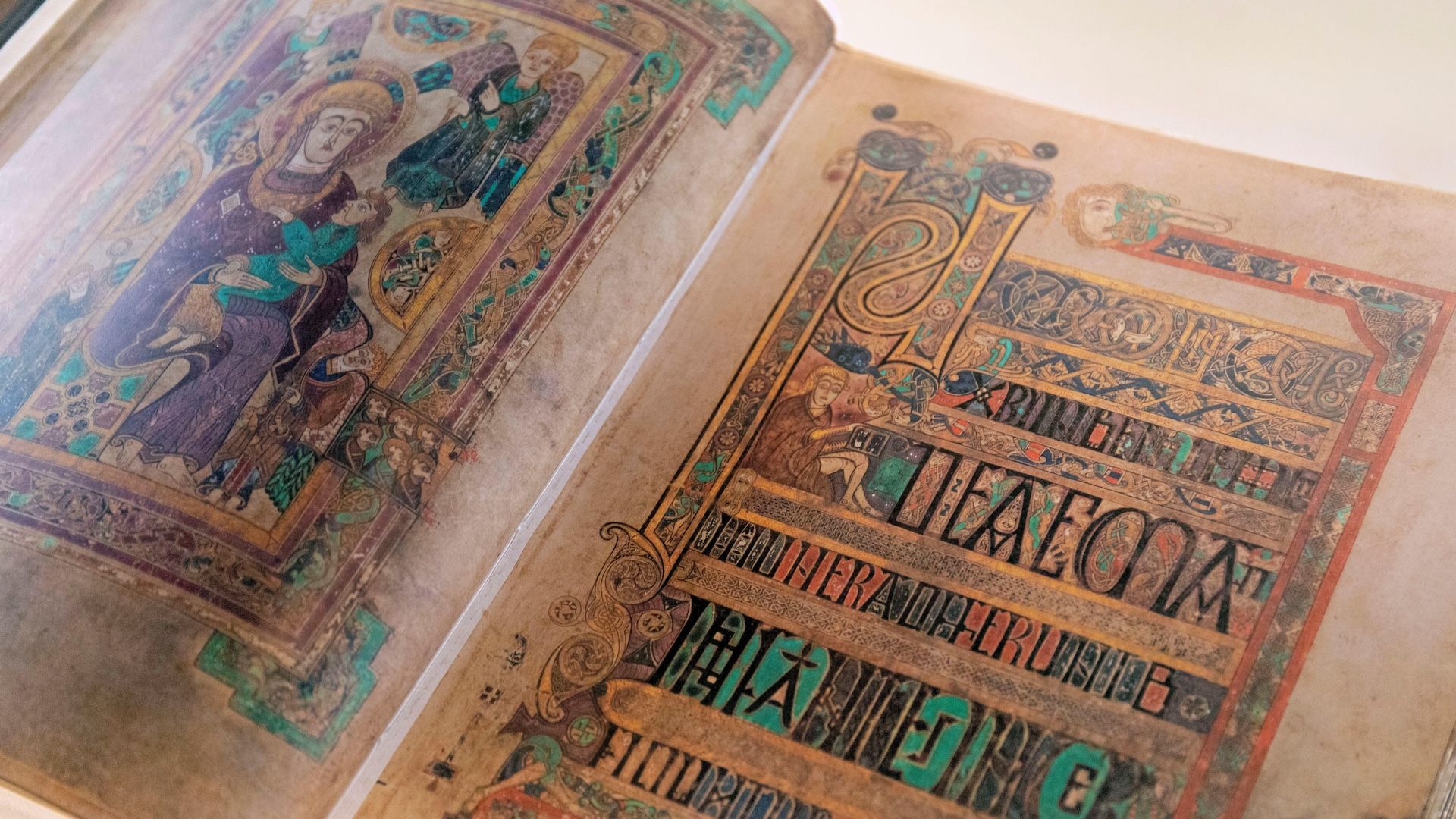

The arrival of St. Patrick in the 5th century marked a pivotal turning point, leading to the gradual Christianization of the island. Unlike many parts of Europe, Christianity in Ireland blended with existing pagan traditions, leading to a unique monastic culture. Ireland entered a Golden Age of Monasticism [2], becoming a beacon of scholarship, art, and literacy during Europe’s Dark Ages. Monasteries like Clonmacnoise produced illuminated manuscripts such as the world-renowned Book of Kells, and Irish monks embarked on missionary journeys across Europe.

Viking Invasions and Settlements (c. 8th-10th Centuries)

From the late 8th century, Viking longships began to raid Ireland’s shores, initially targeting wealthy monastic sites. While disruptive, the Vikings also laid the foundations for Ireland’s first towns, including Dublin (Áth Cliath), Wexford, Waterford, Cork, and Limerick, transforming the island’s economic and urban landscape. Their power was significantly curtailed following the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, led by High King Brian Boru.

Norman Invasion and English Rule Begins (12th Century)

The year 1169 marked another seismic shift. Following an invitation from the exiled King of Leinster, Dermot MacMurrough, Anglo-Norman knights arrived, led by Richard de Clare (Strongbow). This heralded the beginning of centuries of English involvement and eventual direct rule. Initially confined to an area around Dublin known as ‘The Pale,’ English influence gradually extended, introducing new feudal systems and legal frameworks that clashed with native Gaelic traditions. This period is crucial to understanding the ancient history of Ireland explained.

The Long Road to Sovereignty: A Brief History of Irish Independence

English Ascendancy and Religious Division (16th-18th Centuries)

The Tudor monarchs, particularly Elizabeth I and James I, pursued a policy of complete conquest, suppressing Gaelic culture and traditional chieftaincies. The Plantations, particularly in Ulster, saw the systematic seizure of Irish land and its redistribution to Protestant settlers from England and Scotland, profoundly altering demographics and laying seeds for future conflict. The subsequent Penal Laws, enacted from the late 17th century, systematically discriminated against Catholics and, to a lesser extent, Presbyterians, stripping them of land, political rights, and educational opportunities. Despite this oppression, nationalist sentiment grew, fueled by Enlightenment ideals, epitomized by figures like Wolfe Tone and the United Irishmen, who sought a united, independent Ireland free from British rule.

The Act of Union (1801)

Following the failed 1798 Rebellion, the British government abolished the Irish Parliament, enacting the Act of Union, which brought Ireland directly under Westminster rule. This move, intended to prevent further rebellion and consolidate British power, was deeply unpopular with many Irish nationalists. The 19th century saw the rise of political movements, notably Daniel O’Connell’s campaign for Catholic Emancipation, which eventually secured greater rights for Catholics.

The Great Famine (An Gorta Mór, 1845-1849)

A catastrophic potato blight triggered the Great Famine, or An Gorta Mór, a period of unimaginable suffering. Despite Ireland being a net exporter of food, British government policies were widely seen as inadequate, leading to mass starvation, disease, and forced emigration. Over a million people died, and another million emigrated, profoundly reshaping Ireland’s demographics and intensifying anti-British sentiment. This tragedy became a defining moment in the quest for a brief history of Irish independence.

Nationalist Movements and Revolutionary Periods (Late 19th – Early 20th Centuries)

The late 19th century saw the emergence of diverse nationalist movements. The Home Rule Movement advocated for self-governance within the British Empire, gaining significant political traction. Concurrently, a Cultural Revival championed Irish language (Gaelic League), literature, and theatre (Abbey Theatre), reinforcing a distinct Irish identity. However, frustration with slow progress led to more radical actions. The Easter Rising of 1916, though militarily a failure, proved a pivotal moment, shifting public opinion towards full independence. This culminated in the War of Independence (1919-1921), an Anglo-Irish conflict fought between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces.

Partition and the Irish Free State (1921-1922)

The War of Independence ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921 [3]. This established the Irish Free State, a dominion within the British Empire comprising 26 southern counties, while six northern counties, predominantly Protestant, remained part of the United Kingdom as Northern Ireland. This partition, deeply contentious, immediately led to the Irish Civil War (1922-1923) between pro-Treaty and anti-Treaty factions, a bitter conflict that claimed more lives than the War of Independence and left a lasting scar on the nation.

Evolution to Republic of Ireland (1937/1949)

Over the subsequent decades, the Irish Free State gradually distanced itself from Britain. In 1937, a new constitution (Bunreacht na hÉireann) was adopted, replacing the Free State with “Éire” and establishing the office of President, effectively creating a republic in all but name. The formal declaration of the Republic of Ireland came in 1949, asserting complete sovereignty and withdrawing from the Commonwealth.

Divided Loyalties: The History of the Northern Ireland Conflict Explained (The Troubles)

Roots of the Conflict (Post-Partition)

The partition of Ireland left a legacy of deep division in Northern Ireland. The new state was designed with a Protestant Unionist majority, who wished to remain part of the UK, and a significant Catholic Nationalist/Republican minority, who aspired to a united Ireland. Decades of discrimination against the Catholic community in areas like housing, employment, policing, and electoral gerrymandering fueled resentment and a sense of second-class citizenship [4].

Escalation and Key Events of The Troubles (Late 1960s – 1990s)

In the late 1960s, a peaceful Civil Rights Movement, inspired by its American counterpart, emerged to challenge this systemic discrimination. Its peaceful protests were often met with state violence, leading to a rapid escalation. The arrival of the British Army in 1969, initially welcomed by some, soon became a point of contention. Paramilitary groups, notably the Provisional IRA (Republican) and the UDA/UVF (Loyalist), emerged or re-emerged, engaging in a campaign of bombings, assassinations, and sectarian violence. Key events like Internment (imprisonment without trial), Bloody Sunday (1972, where British soldiers shot unarmed civil rights marchers), and the imposition of Direct Rule from Westminster further inflamed the conflict. The 1981 Hunger Strikes, where republican prisoners died protesting for political status, garnered significant international attention and renewed support for paramilitary groups. Various attempts at political solutions, such as the Sunningdale Agreement (1973) and the Anglo-Irish Agreement (1985), failed to achieve lasting peace. This period truly defines the history of Northern Ireland conflict explained.

The Peace Process and Good Friday Agreement (1998)

Decades of violence, coupled with tireless efforts from politicians, community leaders, and international mediators (including the US), slowly paved the way for peace. Secret talks, ceasefires by paramilitary groups, and painstaking negotiations culminated in the signing of the Good Friday Agreement (also known as the Belfast Agreement) on April 10, 1998 [5]. This landmark agreement established a power-sharing government in Northern Ireland, based on principles of consent (the right of the people of Northern Ireland to determine their own status), North-South cooperation with the Republic of Ireland, and the decommissioning of paramilitary weapons.

Post-Agreement Northern Ireland

While the Good Friday Agreement largely ended the widespread violence, Northern Ireland continues to navigate challenges. Power-sharing has seen periods of suspension, and sectarianism, though diminished, persists in some communities. Dealing with the legacy of the Troubles – unresolved issues of justice, victims’ rights, and truth – remains a complex task. More recently, Brexit has introduced new complexities, particularly regarding the Irish border and its potential impact on the peace process, highlighting the fragility and importance of ongoing reconciliation efforts.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Resilience and Ongoing Evolution

From the megalithic wonders of Newgrange to the establishment of the modern Republic and the ongoing peace in Northern Ireland, Ireland’s history is a testament to its people’s enduring spirit. We’ve traced a path through millennia, witnessing cultural flourishing, periods of brutal oppression, and remarkable triumphs of self-determination. The echoes of these historical events continue to shape modern Irish identity, politics, and its relationship with the UK. The journey from ancient kingdoms to a sovereign republic, and the complex peace in Northern Ireland, are integral to understanding the nuances of the island today. While challenges remain, particularly in navigating post-Brexit realities and fully addressing sectarian divides, Ireland’s future is one of continued reconciliation, economic growth, and cultural vibrancy. It remains a nation rich in heritage, adapting to new global challenges while holding firm to its unique place in the world. The saga of the Emerald Isle is not merely a chronicle of events, but a living narrative of resilience, identity, and the relentless human pursuit of peace and self-determination.

References

- [1] Ancient Ireland Chronicles: Pre-Celtic Era

- [2] Celtic Mythos: Early Christian Ireland

- [3] Irish Independence Archive: Treaty Documents

- [4] Historical Ireland Studies: Partition Effects

- [5] Troubles History: Good Friday Explained