A Comprehensive Journey Through Canada’s Rich History: From Indigenous Roots to Modern Nationhood

Canada’s identity is a complex tapestry woven from diverse peoples, vast landscapes, and a compelling, often challenging, past. More than just a collection of provinces and territories, it’s a nation shaped by millennia of human presence and profound historical shifts. This article will explore the deep indigenous roots that form the bedrock of Canadian society, the transformative colonial period that introduced new cultures and conflicts, the pivotal moment of Confederation that forged a new nation, and the ongoing evolution towards reconciliation, highlighting major events and significant figures that shaped the country we know today. Join us on a journey through pre-contact Indigenous societies, European arrival, the arduous process of nation-building, and contemporary efforts to address historical injustices and build a more inclusive future.

I. The Deep Roots: Indigenous History Before European Contact

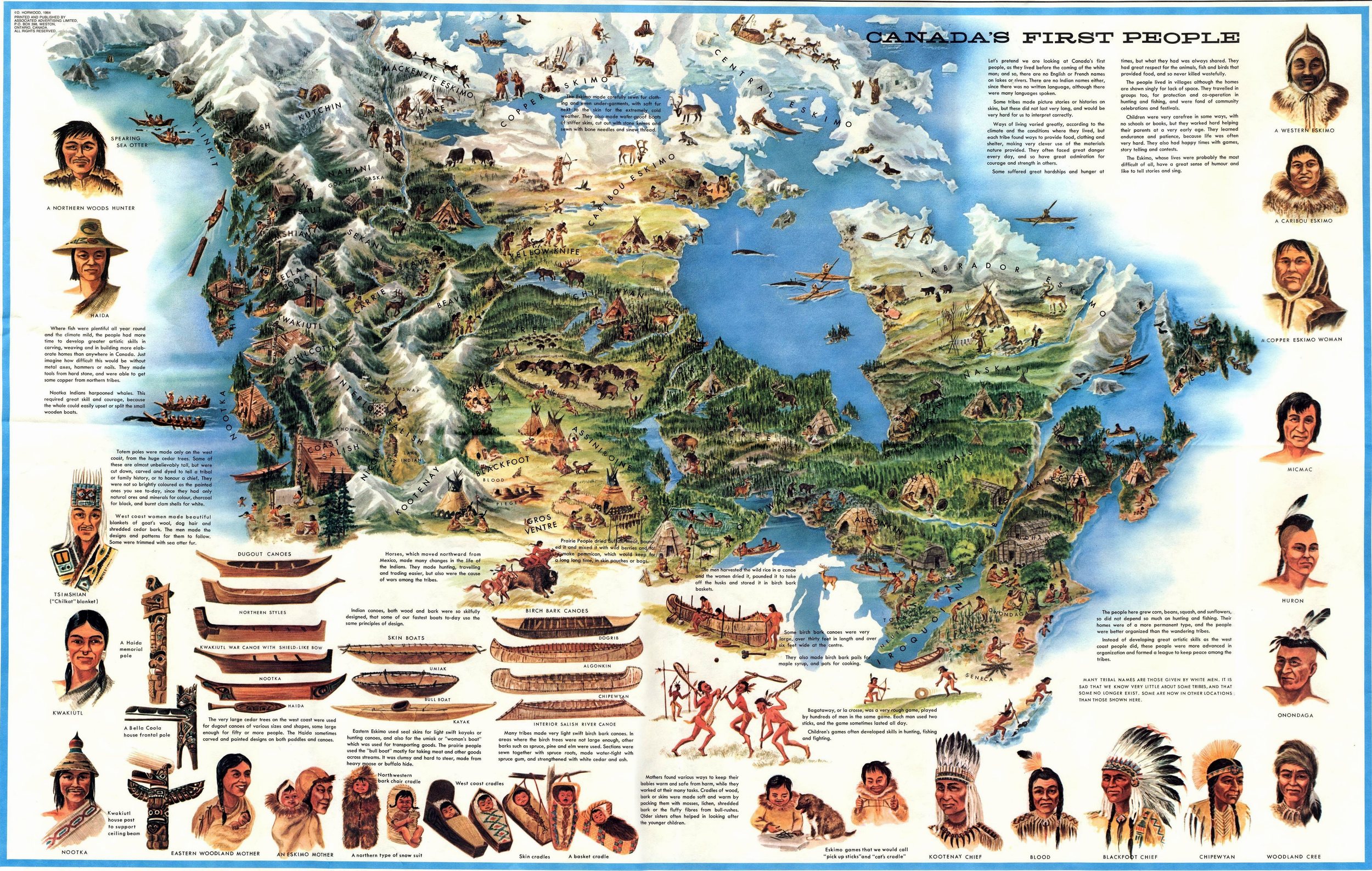

Long before European explorers sighted its shores, the land now known as Canada was home to a mosaic of vibrant and complex Indigenous societies. These peoples, with their distinct cultures, languages, and traditions, thrived across vast and varied landscapes.

A. Diverse Nations and Cultures

Pre-contact Canada was a land of incredible human diversity. Major Indigenous groups included the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) known for their sophisticated political structures in the Eastern Woodlands, the Anishinaabe (Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi) of the Great Lakes region, the Cree and Dene of the boreal forests and plains, and the Inuit who adapted ingeniously to the Arctic environment. Along the Pacific Coast, nations like the Coastal Salish, Haida, and Tsimshian developed rich artistic traditions and complex social hierarchies. Each nation possessed unique governance structures, economies deeply tied to their environment (e.g., hunting, fishing, agriculture), and profound spiritual beliefs that emphasized harmony with nature [1].

B. Advanced Societies and Oral Traditions

These were not simple societies; they were advanced civilizations with sophisticated societal organization, extensive trade networks spanning thousands of kilometers, and innovative agricultural practices that sustained large populations, particularly in the south. Knowledge and history were primarily transmitted through rich oral traditions, including stories, songs, ceremonies, and epic narratives, ensuring the continuity of cultural identity and wisdom across generations. These oral histories are invaluable sources for understanding Indigenous perspectives on their past and present.

II. European Arrival and the Dawn of Colonialism (15th – 18th Centuries)

The arrival of Europeans marked a profound turning point, initiating centuries of dramatic change for Indigenous peoples and the continent.

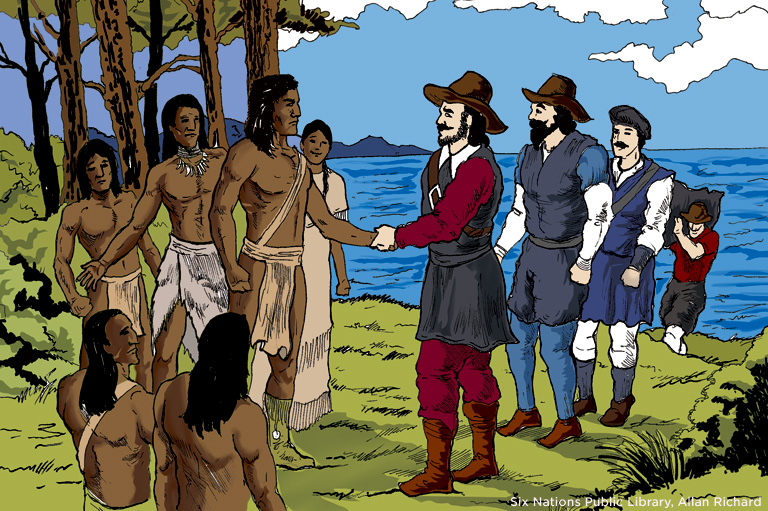

A. Early Explorers and First Encounters

While a brief Viking presence existed around 1000 CE in Newfoundland, sustained European contact began in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Key figures include John Cabot, who explored the Atlantic coast for England in 1497, and Jacques Cartier, who made three voyages for France starting in 1534, exploring the St. Lawrence River. Later, Samuel de Champlain established Port Royal in 1605 and Quebec City in 1608, laying the foundation for New France. Initial interactions with Indigenous peoples were often characterized by trade in furs and goods, and strategic alliances, but also tragically by the introduction of European diseases like smallpox, which decimated Indigenous populations that had no immunity.

B. New France and British Expansion

The 17th and 18th centuries saw the development of New France, largely centered around the lucrative fur trade and a unique seigneurial system of land division. However, growing British colonial ambitions led to increasing conflicts. The decisive conflict was the Seven Years’ War (known as the French and Indian War in North America), which culminated in the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in 1759. Significant figures like French General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm and British General James Wolfe famously died during this battle, leading to the fall of Quebec City and eventually, in 1763, the cession of New France to Britain [2].

C. Profound Impact on Indigenous Peoples

The advent of colonialism had a devastating and enduring impact on Indigenous peoples. They faced widespread displacement from their traditional territories, depletion of vital resources due to European economic activities, and the catastrophic effects of disease, which led to immense population decline. Early treaties, such as the Treaties of Peace and Friendship in the Maritimes, were signed, but their interpretations and consequences often varied widely, frequently disadvantaging Indigenous nations.

III. The Path to Confederation and Nation-Building (18th – 19th Centuries)

Following the British conquest, the colonies on the northern half of North America began a complex journey toward self-governance and, eventually, nationhood.

A. Post-Conquest British Rule

British rule initially brought changes to the former New France. The Quebec Act of 1774 was a significant piece of legislation, preserving French civil law, the seigneurial system, and religious freedom for Roman Catholics, thereby securing the loyalty of French Canadians during the American Revolution. The Constitutional Act of 1791 further shaped governance, dividing Quebec into Upper Canada (English-speaking, largely Loyalist) and Lower Canada (French-speaking), each with its own elected assembly. The War of 1812, fought between Britain (with its Canadian and Indigenous allies) and the United States, played a crucial role in fostering a nascent sense of shared Canadian identity among diverse settlers, as they united against a common external threat.

B. Calls for Self-Governance and Political Reform

Despite these acts, political tensions simmered, culminating in the Rebellions of 1837-38 in both Upper and Lower Canada, driven by demands for responsible government and democratic reform. In response, Lord Durham’s Report (1839) recommended the union of the two Canadas and the assimilation of French Canadians. This led to the Act of Union (1840), creating the Province of Canada, which, while failing to achieve assimilation, laid some groundwork for broader political unity.

C. The Fathers of Confederation and Their Vision

By the mid-19th century, several factors converged to push for a larger union: fear of American expansion, the need for economic growth and a common market, and political deadlock in the Province of Canada. Visionary leaders, often referred to as the Fathers of Confederation, emerged to champion the cause. Key figures included Sir John A. Macdonald, a shrewd politician who became Canada’s first Prime Minister; George-Étienne Cartier, who ensured Quebec’s distinct identity would be preserved within the new union; and George Brown, an advocate for representation by population. Through a series of conferences – Charlottetown (1864), Quebec (1864), and London (1866) – these leaders hammered out the details of the new nation.

The historical significance of Confederation in 1867 cannot be overstated. On July 1st, 1867, the British North America Act (now the Constitution Act, 1867) created the Dominion of Canada, initially comprising four provinces: Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. This marked the birth of a new country, driven by motivations such as political stability, economic integration, and a desire to resist American annexation. Immediately, the new Dominion faced challenges, including westward expansion and defining its relationship with its Indigenous populations [3].

IV. Canada’s Evolution: From Dominion to Modern Nation (Late 19th – 20th Centuries)

The new Dominion quickly began to expand, dramatically reshaping the North American landscape and its own identity.

A. Westward Expansion and Indigenous Dispossession

A central pillar of the new nation’s vision was westward expansion. The construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was instrumental in connecting the country from coast to coast, facilitating settlement and resource extraction. However, this expansion came at an enormous cost to Indigenous peoples. The signing of the Numbered Treaties (1871-1921) often involved significant land cessions by First Nations under duress, and promises made were frequently not honored, leading to a profound impact on First Nations’ land rights and way of life.

The Indian Act of 1876 further codified and controlled the lives of First Nations peoples, stripping them of traditional governance and imposing a paternalistic system. Most tragically, the Residential Schools system, mandatory for Indigenous children, aimed to assimilate them into Euro-Canadian culture, leading to widespread abuse, trauma, and the loss of language and culture. This dark chapter has left a devastating legacy that continues to affect generations. The Métis Nation, a distinct Indigenous people of mixed heritage, also faced significant struggles for their rights and land, notably led by Louis Riel in the Red River (1869-70) and North-West (1885) Rebellions [4].

B. World Wars and Global Identity

The 20th century saw Canada step onto the global stage. Its significant contributions to World War I, particularly at battles like Vimy Ridge, fostered a stronger sense of national identity distinct from Britain. In World War II, Canada again played a vital role, contributing immense resources and manpower, exemplified by events like the Dieppe Raid. These sacrifices solidified Canada’s international standing and led to greater autonomy from Britain, formally recognized by the Statute of Westminster in 1931, which granted full legislative independence.

C. Post-War Growth and Social Change

The post-war era brought economic prosperity and significant social transformation. In Quebec, the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s saw a rapid modernization of Quebec society, leading to a strong surge in Quebec nationalism and a desire for greater autonomy. Nationally, Canada embraced multiculturalism as a national policy, celebrating its diverse immigrant populations. The mid-to-late 20th century also witnessed significant social reforms and the expansion of the welfare state. A towering figure of this era was Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau, who played a pivotal role in the patriation of the Constitution in 1982, which included the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, guaranteeing fundamental rights and freedoms for all Canadians [5].

V. Contemporary Canada: Reconciliation and Identity in the 21st Century

As Canada entered the 21st century, its historical past, particularly concerning Indigenous peoples, came increasingly into focus, leading to a profound national reckoning.

A. The Journey Towards Reconciliation

A cornerstone of contemporary Canada is the journey towards reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. The establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 2008 was a crucial step, documenting the devastating impacts of residential schools and issuing 94 Calls to Action. This has been followed by official government apologies for historical injustices, including the residential school system and the Sixties Scoop. While progress is ongoing and challenges remain, there are continuous efforts to build healing and foster meaningful nation-to-nation relationships with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, recognizing their inherent rights and self-determination.

B. Evolving National Identity

Canada’s national identity continues to evolve. On the global stage, Canada is often recognized for its commitment to peacekeeping, diplomacy, and environmental initiatives. Internally, the importance of diversity, inclusion, and human rights remains central to its self-image. Debates about national memory, symbols, and future direction are ongoing, reflecting a dynamic society grappling with its past and striving to build a more just and equitable future for all who call this land home.

Conclusion

Canada’s history is a profound and complex narrative, stretching back thousands of years to the diverse and thriving Indigenous nations who were the original custodians of this land. The arrival of Europeans ushered in a period of colonialism that dramatically reshaped the continent, leading to the formation of New France and, eventually, British North America. The pivotal moment of Confederation in 1867 forged a new nation, but its expansion came with immense costs for Indigenous peoples. Through two World Wars and significant social changes, Canada evolved from a British Dominion into a modern, multicultural nation. Today, the enduring legacies of major events and the contributions of significant figures from all backgrounds continue to shape its identity, while the journey towards reconciliation with Indigenous peoples remains a defining challenge and opportunity.

Understanding this intricate past – its triumphs and its tragedies – is crucial for shaping a more just, equitable, and informed future for all Canadians. It’s a continuous process of learning, reflection, and building better relationships for generations to come.

References

- [1] Canadian Heritage Info. (n.d.). Historical Timelines: Indigenous Sovereignty.

- [2] Archives Canada. (n.d.). Colonial Era Documents.

- [3] National Historical Museum. (n.d.). Exhibitions: Confederation Dream.

- [4] University of Canadian Studies. (n.d.). Journal: Articles: First Nations Resilience.

- [5] Government of Canada. (n.d.). History: Key Figures in Nation Building.